Post by LWPD on Mar 30, 2013 8:58:29 GMT -5

Here's a great breakdown on factors likely to continue to push the value of the U.S. Dollar higher in the years to come. Several excellent points are made with regards to the power and influence that comes from controlling the world's reserve currency. Unlike other countries, the unique scope of America's economic power isn't limited to the size of its domestic economy, but of the entire global economic system that it acts to facilitate. In context, this is the difference between a $15.8 trillion system (domestic GDP) and a $210 trillion system (global GDP which uses money the U.S. can electronically create at will, and then export abroad in exchange for real goods and services).

Courtesy of The Big Picture

Tailwinds Pushing U.S. Dollar Higher

By Charles Hugh Smith

If we shed our fixation with the Fed and look at global supply and demand, we get a clearer understanding of the tailwinds driving the U.S. dollar higher.

I know this is as welcome in many circles as a flashbang tossed on the table in a swank dinner party, but the U.S. dollar is going a lot higher over the next few years. For a variety of reasons, many observers expect the dollar to decline against other currencies and gold, the one apples-to-apples measure of a currency’s international purchasing power.

The tailwinds pushing the dollar higher are less intuitively appealing than the reasons given for its coming decline:

1. The Federal Reserve printing another trillion dollars (expanding its balance sheet) will devalue the dollar because money supply is expanding faster than the real economy.

2. The Fed is printing money with the intent of devaluing the dollar to make U.S. exports more competitive globally and thereby boost the domestic economy.

Let’s examine each point.

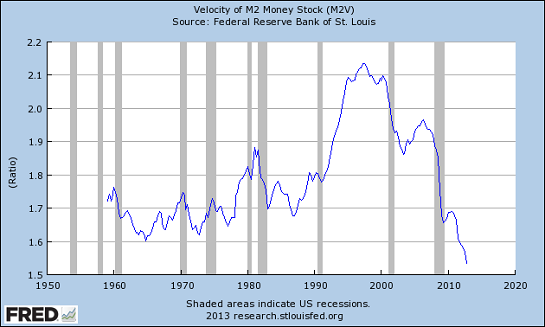

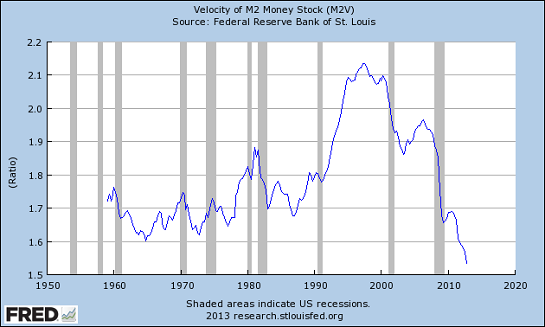

1A. If much of the Fed’s new money ends up as bank reserves, it is “dead money” and not a factor in the real economy. Fact: money velocity is tanking:

1B. Money is being destroyed by deleveraging and writedowns. This is taking money out of the real economy while the Fed’s new money flows to banks.

1C. The purchasing power of the dollar is set by international supply and demand, not the Fed’s balance sheet or the domestic money supply.

As for point 2:

2A. Exports are 13% of the economy. A stronger dollar would reduce the cost of oil, helping 100% of the economy, including exporters. Why would the Fed damage the entire economy to boost exports from 13% to 14% of the domestic economy? It makes no sense.

2B. Most U.S. exports are either must-have’s (soybeans, grain, etc.) that buyers will buy at any price because they need to feed their people (and recall that agricultural commodities often fluctuate in a wide price band due to supply-demand issues, so if they rise 50% due to a rising dollar, it’s no different than price increases due to droughts) or they are products that are counted as exports but largely made with non-U.S. parts.

How much of the iPad is actually made in the U.S.? Basically zero. Is it counted as an export? Yes. How much of a Boeing 787 airliner is actually manufactured in the U.S.? Perhaps a third. Sorting out what is actually made in the U.S. within complex corporate supply chains is not easy, and the results are often misleading.

2C. Many exports are made and sold in other countries by U.S. corporations, and so the sales are booked in the local currency. The dollar could rise or fall by 50% and most of the U.S. corporate supply chain and sales would not be affected because many of the goods and services are sourced and sold in other nations’ currencies. The only time the dollar makes an appearance is in the profit-loss statement at home.

Americans tend not to know that up to 75% of U.S. corporations’ revenues are generated overseas, in currencies other than the dollar. This may be part of Americans’ famously domestic-centric perspective.

2D. Most importantly, the American Empire needs to control and issue the global reserve currency. The Fed is a handmaiden to the Empire; the Fed’s claims of independence and its “dual mandate” are useful misdirections.

Some analysts mistakenly believe that Fed policies are aimed at boosting the relatively modest export sector (which we have already seen is a convoluted mess of globally supplied parts, sales in other currencies, etc.) from 13% to 14% of the domestic economy.

This overlooks the fact that the most important export of the U.S. is U.S. dollars for international use. I explained some of the dynamics in Understanding the “Exorbitant Privilege” of the U.S. Dollar (November 19, 2012) and What Will Benefit from Global Recession? The U.S. Dollar (October 9, 2012).

Which is easier to export:manufactured goods that require shipping ore and oil halfway around the world, smelting the ore into steel and turning the oil into plastics, laboriously fabricating real products and then shipping the finished manufactured goods to the U.S. where fierce pricing competition strips away much of the premium/profit?Or electronically printing money and exchanging it for real products, steel, oil, etc.?

I think we can safely say that creating money out of thin air and “exporting” that is much easier than actually mining, extracting or manufacturing real goods. This astonishing exchange of conjured money for real goods is the heart of the “exorbitant privilege” that accrues to the issuer of the global reserve currency (U.S. dollar).

It’s important to put the Fed’s $3 trillion balance sheet in a foreign-exchange (FX) and global perspective:

- The FX market trades $3 trillion a day in currencies.

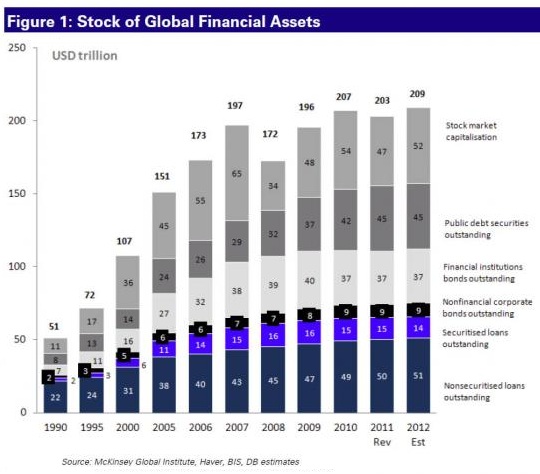

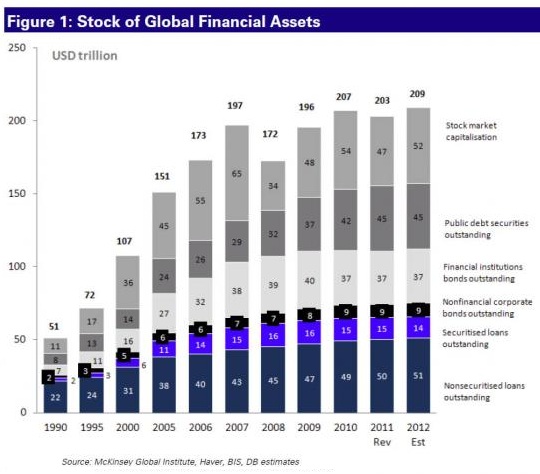

- Global financial assets are estimated at around $210 trillion. The Fed’s balance sheet is 1.5% of global assets.

The key to understanding the dollar and Triffin’s Paradox is that as the global reserve currency, the dollar serves both domestic and international markets. Of the two, the more important market is the international one.

To act as the global reserve currency, a currency must be exported in sufficient size to facilitate the gargantuan trade in a $60 trillion global GDP/ $210 trillion global economy. There are only two ways to export enough currency to be remotely useful:

1. Run massive trade deficits, i.e. import goods and export dollars.

2. Loan massive quantities of dollars to nations that will place the dollars in international circulation.

The famous Marshall Plan that helped Western Europe rebuild its economies was just that: a series of large loans of dollars to dollar-starved economies. This was necessary because the U.S. was running trade surpluses in the postwar era and was therefore not exporting dollars.

This leads to a startling but inescapable conclusion: no exporting nation can issue the global reserve currency. That eliminates the European Union, China, Japan, Russia and every other nation running surpluses or modest deficits.

Many commentators are drawing incorrect conclusions from various attempts to bypass the dollar in settling trade accounts. For example, China is setting up direct exchanges where buyers and sellers can exchange their own currencies for renminbi, eliminating the need for intermediary dollars.

This is widely interpreted as the death knell for the dollar. But this misses the entire point of the reserve currency, which is that it must be available in quantity for everyone to use, not just those doing business with the domestic economy of the issuing nation.

Here’s a practical example. The $100 bill is “money” everywhere in the world, recognizable as both a medium of exchange for gold, other currencies, goods and services, and as a store of value that is priced transparently (often on the black market). For the Chinese renminbi/yuan to replace the dollar as the global reserve currency, China would need to “export” enough currency to grease trade large and small worldwide, and enough electronic money to act as reserves that support domestic lending in nations holding the reserve currency.

This is yet another poorly understood function of the reserve currency: it acts as foreign exchange reserves, backing up the holder’s currency, and as reserves in its central bank that act as collateral for its domestic issuance of credit.

In other words, the U.S. has issued and exported trillions of dollars because this is the necessary grease for global trade, currency stability and issuance of credit by nations holding dollars. The U.S. didn’t run massive trade deficits by accident: it needed to “export” more dollars as the volume of global trade expanded.

Issuing credit and loans in dollars wasn’t enough, so the U.S. exported dollars in exchange for commodities and goods.

For China to issue the global reserve currency, it would have to decouple the yuan from the U.S. dollar and start running deficits on the order of $500 billion a year.

Many observers think China is preparing to back its currency with gold, and they mistakenly conclude (yet again) this would be the death knell for the dollar. But they haven’t thought through how currencies work: their value is ultimately set like everything else, by supply and demand.

In an export-dependent country like China, a gold-backed currency would not be exported in quantity–it wouldn’t be “exported” at all, because China “imports” others’ currencies in exchange for goods.

Assuming some of the gold-backed currency was exported, it would quickly end up in savings accounts or bank vaults, being a proxy for gold. There will be none available for facilitating trade in the $210 trillion global economy.

This dual nature of money trips up many analysts. Establishing a currency that is “as good as gold” but not exporting it in quantity means it will be hoarded as a store of value and be unavailable to facilitate trade. Money has to act both as a store of value and as a means of exchange.

This is why U.S. $100 bills are carefully stored in plastic in distant entrepots of the world, safeguarded as real money, available as a store of value and as a means of exchange.

Currencies can be exchanged in a Forex (FX) marketplace, but the reserve currency is the “winner take all” in the real world. If you hold out an equivalent sum in various currencies around the world, the trader in the stall will likely choose the $100 bill because he is not sure of the value of the other funny-money in his home currency and he knows he can easily exchange the $100 everywhere.

The other currencies might trade on the FX market at some percentage of the dollar, but in the real world they are effectively worthless because there isn’t enough of them available to establish a transparent, truly global market. To do that, a nation has to export monumental quantities of their currency and operate their domestic economy in such a fashion that the currency is recognized as being a store of value.

In a very real sense, every currency is a claim not on the issuing central bank’s balance sheet but on the entire economy of the issuing nation.

All this leads to two powerful tailwinds to the value of the dollar. One is simply supply and demand: as the global economy slides into recession, trade volumes decline, and the U.S. deficit shrinks. (It’s already $250 billion less than was “exported” in 2006.) That will leave fewer dollars available on the global market.

In the case of the U.S., which exports large quantities of what the world needs (grain, soy beans, etc.) while buying mostly stuff that is falling in price in recession (oil, surplus manufactured goods, etc.), the trade deficit could decline significantly. (It is currently around $40 billion a month.)

And what does a declining trade deficit mean? It means fewer dollars are being exported. The global GDP is about $60 trillion, of which about 25% is the U.S. economy. Into this vast sea of trade, the U.S. “exports” about $500 billion in U.S. dollars via the trade deficit. Put in perspective, it isn’t that big compared to the machine it is lubricating.

So what happens when there are fewer dollars being exported? Demand for existing dollars goes up, pushing the “price/cost” of dollars up–basic supply and demand.

The second tailwind is the demand for dollars from those exiting the euro and yen. The abandonment of the euro is already visible in these charts, courtesy of Market Daily Briefing: Peak Euros.

We can anticipate this desire to transfer euros and yen into dollars will only increase as those currencies depreciate. Let’s say, just as an example, $5 trillion in euros starts chasing $1 trillion in available U.S. dollars. What will that do to the value of the dollar?

Some ask why those selling euros won’t buy Chinese yuan. Where are you going to find $1 trillion in yuan? It isn’t even convertible on an open market, and since China is an importer of currency, there isn’t 1 trillion yuan floating around the global marketplace to buy even if you wanted to.

Many people scoff when I suggest the dollar could rise 50% (i.e. the DXY dollar index could climb from its current level around 80 to 120) or even 100% (DXY = 160) in the years ahead. I know it’s the highest order of sacrilege to even murmur this, but if global demand for dollars picks up, the Fed isn’t printing nearly enough to dent the rise in the dollar.

As a lagniappe outrage, consider the domestic fallout from a decline in U.S. stocks and the U.S. economy. The Fed’s precious horde of political capital will leak away, and its ability to print more money will be proscribed by political resistance and a loss of faith in the Fed’s claimed omnipotence.

Any reduction in Fed printing would only limit the quantity of dollars available to global buyers, further pushing up its price on the open market.

Courtesy of The Big Picture

Tailwinds Pushing U.S. Dollar Higher

By Charles Hugh Smith

If we shed our fixation with the Fed and look at global supply and demand, we get a clearer understanding of the tailwinds driving the U.S. dollar higher.

I know this is as welcome in many circles as a flashbang tossed on the table in a swank dinner party, but the U.S. dollar is going a lot higher over the next few years. For a variety of reasons, many observers expect the dollar to decline against other currencies and gold, the one apples-to-apples measure of a currency’s international purchasing power.

The tailwinds pushing the dollar higher are less intuitively appealing than the reasons given for its coming decline:

1. The Federal Reserve printing another trillion dollars (expanding its balance sheet) will devalue the dollar because money supply is expanding faster than the real economy.

2. The Fed is printing money with the intent of devaluing the dollar to make U.S. exports more competitive globally and thereby boost the domestic economy.

Let’s examine each point.

1A. If much of the Fed’s new money ends up as bank reserves, it is “dead money” and not a factor in the real economy. Fact: money velocity is tanking:

1B. Money is being destroyed by deleveraging and writedowns. This is taking money out of the real economy while the Fed’s new money flows to banks.

1C. The purchasing power of the dollar is set by international supply and demand, not the Fed’s balance sheet or the domestic money supply.

As for point 2:

2A. Exports are 13% of the economy. A stronger dollar would reduce the cost of oil, helping 100% of the economy, including exporters. Why would the Fed damage the entire economy to boost exports from 13% to 14% of the domestic economy? It makes no sense.

2B. Most U.S. exports are either must-have’s (soybeans, grain, etc.) that buyers will buy at any price because they need to feed their people (and recall that agricultural commodities often fluctuate in a wide price band due to supply-demand issues, so if they rise 50% due to a rising dollar, it’s no different than price increases due to droughts) or they are products that are counted as exports but largely made with non-U.S. parts.

How much of the iPad is actually made in the U.S.? Basically zero. Is it counted as an export? Yes. How much of a Boeing 787 airliner is actually manufactured in the U.S.? Perhaps a third. Sorting out what is actually made in the U.S. within complex corporate supply chains is not easy, and the results are often misleading.

2C. Many exports are made and sold in other countries by U.S. corporations, and so the sales are booked in the local currency. The dollar could rise or fall by 50% and most of the U.S. corporate supply chain and sales would not be affected because many of the goods and services are sourced and sold in other nations’ currencies. The only time the dollar makes an appearance is in the profit-loss statement at home.

Americans tend not to know that up to 75% of U.S. corporations’ revenues are generated overseas, in currencies other than the dollar. This may be part of Americans’ famously domestic-centric perspective.

2D. Most importantly, the American Empire needs to control and issue the global reserve currency. The Fed is a handmaiden to the Empire; the Fed’s claims of independence and its “dual mandate” are useful misdirections.

Some analysts mistakenly believe that Fed policies are aimed at boosting the relatively modest export sector (which we have already seen is a convoluted mess of globally supplied parts, sales in other currencies, etc.) from 13% to 14% of the domestic economy.

This overlooks the fact that the most important export of the U.S. is U.S. dollars for international use. I explained some of the dynamics in Understanding the “Exorbitant Privilege” of the U.S. Dollar (November 19, 2012) and What Will Benefit from Global Recession? The U.S. Dollar (October 9, 2012).

Which is easier to export:manufactured goods that require shipping ore and oil halfway around the world, smelting the ore into steel and turning the oil into plastics, laboriously fabricating real products and then shipping the finished manufactured goods to the U.S. where fierce pricing competition strips away much of the premium/profit?Or electronically printing money and exchanging it for real products, steel, oil, etc.?

I think we can safely say that creating money out of thin air and “exporting” that is much easier than actually mining, extracting or manufacturing real goods. This astonishing exchange of conjured money for real goods is the heart of the “exorbitant privilege” that accrues to the issuer of the global reserve currency (U.S. dollar).

It’s important to put the Fed’s $3 trillion balance sheet in a foreign-exchange (FX) and global perspective:

- The FX market trades $3 trillion a day in currencies.

- Global financial assets are estimated at around $210 trillion. The Fed’s balance sheet is 1.5% of global assets.

The key to understanding the dollar and Triffin’s Paradox is that as the global reserve currency, the dollar serves both domestic and international markets. Of the two, the more important market is the international one.

To act as the global reserve currency, a currency must be exported in sufficient size to facilitate the gargantuan trade in a $60 trillion global GDP/ $210 trillion global economy. There are only two ways to export enough currency to be remotely useful:

1. Run massive trade deficits, i.e. import goods and export dollars.

2. Loan massive quantities of dollars to nations that will place the dollars in international circulation.

The famous Marshall Plan that helped Western Europe rebuild its economies was just that: a series of large loans of dollars to dollar-starved economies. This was necessary because the U.S. was running trade surpluses in the postwar era and was therefore not exporting dollars.

This leads to a startling but inescapable conclusion: no exporting nation can issue the global reserve currency. That eliminates the European Union, China, Japan, Russia and every other nation running surpluses or modest deficits.

Many commentators are drawing incorrect conclusions from various attempts to bypass the dollar in settling trade accounts. For example, China is setting up direct exchanges where buyers and sellers can exchange their own currencies for renminbi, eliminating the need for intermediary dollars.

This is widely interpreted as the death knell for the dollar. But this misses the entire point of the reserve currency, which is that it must be available in quantity for everyone to use, not just those doing business with the domestic economy of the issuing nation.

Here’s a practical example. The $100 bill is “money” everywhere in the world, recognizable as both a medium of exchange for gold, other currencies, goods and services, and as a store of value that is priced transparently (often on the black market). For the Chinese renminbi/yuan to replace the dollar as the global reserve currency, China would need to “export” enough currency to grease trade large and small worldwide, and enough electronic money to act as reserves that support domestic lending in nations holding the reserve currency.

This is yet another poorly understood function of the reserve currency: it acts as foreign exchange reserves, backing up the holder’s currency, and as reserves in its central bank that act as collateral for its domestic issuance of credit.

In other words, the U.S. has issued and exported trillions of dollars because this is the necessary grease for global trade, currency stability and issuance of credit by nations holding dollars. The U.S. didn’t run massive trade deficits by accident: it needed to “export” more dollars as the volume of global trade expanded.

Issuing credit and loans in dollars wasn’t enough, so the U.S. exported dollars in exchange for commodities and goods.

For China to issue the global reserve currency, it would have to decouple the yuan from the U.S. dollar and start running deficits on the order of $500 billion a year.

Many observers think China is preparing to back its currency with gold, and they mistakenly conclude (yet again) this would be the death knell for the dollar. But they haven’t thought through how currencies work: their value is ultimately set like everything else, by supply and demand.

In an export-dependent country like China, a gold-backed currency would not be exported in quantity–it wouldn’t be “exported” at all, because China “imports” others’ currencies in exchange for goods.

Assuming some of the gold-backed currency was exported, it would quickly end up in savings accounts or bank vaults, being a proxy for gold. There will be none available for facilitating trade in the $210 trillion global economy.

This dual nature of money trips up many analysts. Establishing a currency that is “as good as gold” but not exporting it in quantity means it will be hoarded as a store of value and be unavailable to facilitate trade. Money has to act both as a store of value and as a means of exchange.

This is why U.S. $100 bills are carefully stored in plastic in distant entrepots of the world, safeguarded as real money, available as a store of value and as a means of exchange.

Currencies can be exchanged in a Forex (FX) marketplace, but the reserve currency is the “winner take all” in the real world. If you hold out an equivalent sum in various currencies around the world, the trader in the stall will likely choose the $100 bill because he is not sure of the value of the other funny-money in his home currency and he knows he can easily exchange the $100 everywhere.

The other currencies might trade on the FX market at some percentage of the dollar, but in the real world they are effectively worthless because there isn’t enough of them available to establish a transparent, truly global market. To do that, a nation has to export monumental quantities of their currency and operate their domestic economy in such a fashion that the currency is recognized as being a store of value.

In a very real sense, every currency is a claim not on the issuing central bank’s balance sheet but on the entire economy of the issuing nation.

All this leads to two powerful tailwinds to the value of the dollar. One is simply supply and demand: as the global economy slides into recession, trade volumes decline, and the U.S. deficit shrinks. (It’s already $250 billion less than was “exported” in 2006.) That will leave fewer dollars available on the global market.

In the case of the U.S., which exports large quantities of what the world needs (grain, soy beans, etc.) while buying mostly stuff that is falling in price in recession (oil, surplus manufactured goods, etc.), the trade deficit could decline significantly. (It is currently around $40 billion a month.)

And what does a declining trade deficit mean? It means fewer dollars are being exported. The global GDP is about $60 trillion, of which about 25% is the U.S. economy. Into this vast sea of trade, the U.S. “exports” about $500 billion in U.S. dollars via the trade deficit. Put in perspective, it isn’t that big compared to the machine it is lubricating.

So what happens when there are fewer dollars being exported? Demand for existing dollars goes up, pushing the “price/cost” of dollars up–basic supply and demand.

The second tailwind is the demand for dollars from those exiting the euro and yen. The abandonment of the euro is already visible in these charts, courtesy of Market Daily Briefing: Peak Euros.

We can anticipate this desire to transfer euros and yen into dollars will only increase as those currencies depreciate. Let’s say, just as an example, $5 trillion in euros starts chasing $1 trillion in available U.S. dollars. What will that do to the value of the dollar?

Some ask why those selling euros won’t buy Chinese yuan. Where are you going to find $1 trillion in yuan? It isn’t even convertible on an open market, and since China is an importer of currency, there isn’t 1 trillion yuan floating around the global marketplace to buy even if you wanted to.

Many people scoff when I suggest the dollar could rise 50% (i.e. the DXY dollar index could climb from its current level around 80 to 120) or even 100% (DXY = 160) in the years ahead. I know it’s the highest order of sacrilege to even murmur this, but if global demand for dollars picks up, the Fed isn’t printing nearly enough to dent the rise in the dollar.

As a lagniappe outrage, consider the domestic fallout from a decline in U.S. stocks and the U.S. economy. The Fed’s precious horde of political capital will leak away, and its ability to print more money will be proscribed by political resistance and a loss of faith in the Fed’s claimed omnipotence.

Any reduction in Fed printing would only limit the quantity of dollars available to global buyers, further pushing up its price on the open market.